Human Cost of Fast Fashion #NeverForget Rana Plaza

- Urvi Dhar

- Apr 25, 2020

- 3 min read

As atrocities inflicted upon the people of Bangladesh continue, we must remember the Rana Plaza incident that took place on this day, seven years ago. Seven years since the incident, today as the demand faced by the brands whose factories were housed in the Rana Plaza (Matalan, Primark and Walmart among others) reduces, and they pull their orders from these factories, causing serious damage, as consumers we have to ask the question - where is the accountability?

What does it mean for major apparel brands of the likes of CandA, Primark, JC Penney, and other European and American giants to pull their orders out of Bangladesh, in whose sweatshops, a large number of their factories are located? And upon that trajectory of thought, what does it mean for the Bangladeshi workers, who were in one breath toiling under the pressure to complete orders to meet the demands of these giants, and in the next breath, became a face in a crowd of thousands who were instantly left jobless, of course owing to the pandemic. The answer to both these questions, sits comfortably in a situation that is nothing short of apocalyptic.

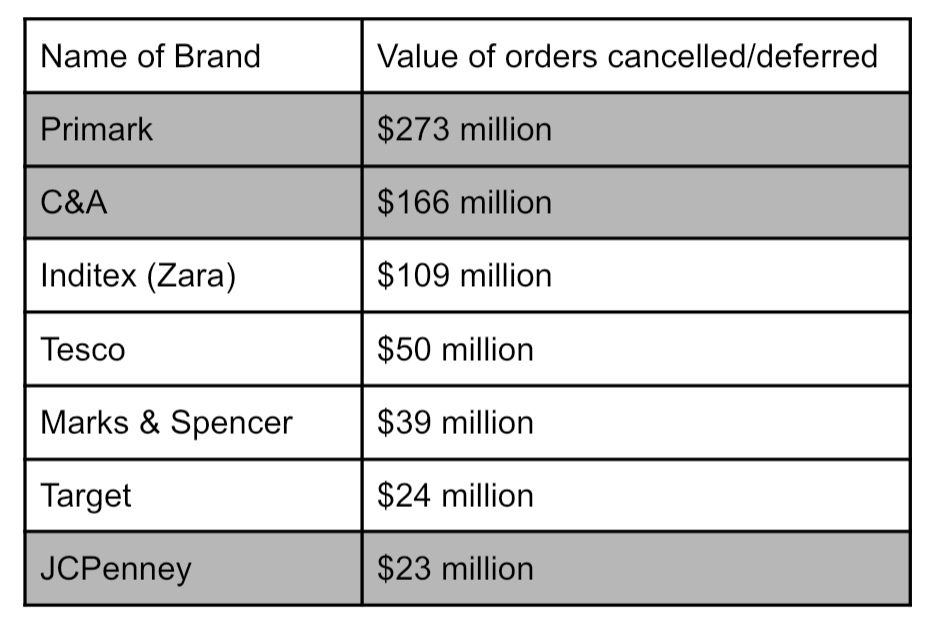

Here’s a table to hold your favourite brands accountable,compiled by the Workers Rights Consortium based on data by the BGMEA as of March 29,2020. From these, Marks&Spencer, Inditex, Target and Tesco have committed to paying in full for orders completed and in production. (You can track which brands are showing responsibility towards their workers here)

Bangladesh provides cheap labour to these apparel brands, in the form of a system that condenses into a number of sweatshops, that invariably subject its workers to extreme exploitation - taking the shape of low wages, long working hours, arbitrary discipline, and the denial of just about any basic human right. As the demand worldwide for the fashion industry has evaporated in the past two months, large brands, upon whom these factories and workers were reliant, have lost their sources of income. To understand the damage that has been done here, one must look at what the apparel industry means to the South Asian nation of Bangladesh. The nation's garment industry is at the heart of its exports. The ready-made garments (RMG) account for 81% of the country’s exports, making it the largest exporter of these garments, second only to China. (As of data from 2018). As these fast fashion giants pull their orders from Bangladesh, the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA) cites the losses to $3.17 billion and 980 million pieces in cancelled orders, amounting to 2.27 million workers affected. This situation is also an eye opener (for those who would like to have their eyes open of course) to the human cost of fast changing fashion trends- which is essentially, the only thing that the fast fashion industry relies upon. The problem of fast fashion is of course a structural problem, a myopic problem. Fuelled by the fast changing needs of the apparel industry, which in turn is fed by us, the people who buy these products, but then we are also heavily influenced by the fashion industry, and the validation that lies in moving with these trends. A vicious cycle.

This also raises the question of whether these brands should be held accountable for the conditions that the workers at their factories work under overseas. There must be an equal burden on the consumers and the manufacturers, to not turn a blind eye to these gross violations. This accountability needs to also be defined by the law, because if the brands are penalised, then the working conditions of the factories would not be slow to change.

Is sustainable fashion the answer to our cries? I think so. As consumers, it is our prerogative to reduce the consumption in this industry, data suggests that 60% of the clothes that are produced are never worn, they are simply discarded. If one was to only buy as much as required, to repurpose, to recycle, to donate, the clothes that would be produced under this decreased consumption, would then also translate to better working conditions, and a better pay.

Comments